Australian student-athlete Kyle Cranston taking the Athletics Decathlon title at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade, among both the most technically nuanced and physically demanding discipline of any sport

Australian student-athlete Kyle Cranston taking the Athletics Decathlon title at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade, among both the most technically nuanced and physically demanding discipline of any sport

In an unassuming badminton and table tennis centre in a nondescript pocket of Melbourne suburbia, two young men are playing table tennis. They jump, dive and parry smash after smash off the bright blue table. The pace is breathtaking. Ping pong balls litter the floor.

During a brief pause, one of the players shakes his head. “I took two days off, and I’m feeling a little rusty.” This is Heming Hu, a member of the team representing Australia at the Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast.

Heming, who goes by Huey, Hu-Dog or Hu-man among his friends, has just celebrated his 24th birthday. This is the first of two three-hour training sessions scheduled for the day.

Also on Heming’s schedule is a 4pm class at Monash University. In addition to his full-time commitment to elite-level table tennis, he’s pursuing a double degree in education and science.

It seems counterintuitive, on first glance. Succeeding at the elite level in sport requires a huge amount of time and commitment. Training and competing are both mentally and physically exhausting. Wouldn’t the added pressure of a university course stretch an athlete too thin?

Years of time, energy and financial resources are typically involved, and from a very early age. Why would an athlete want to jeopardise all this investment by adding university study to the mix?

It turns out that there’s no evidence that simultaneously pursuing studies and sport negatively impacts athletic success. If anything, the opposite may be true.

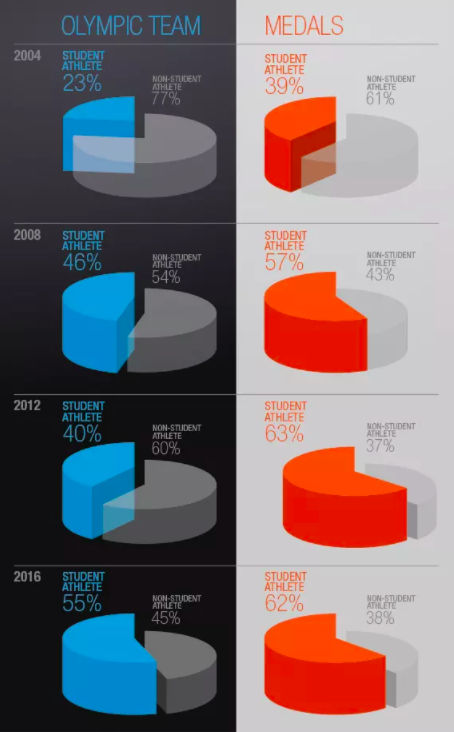

In the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, for example, Australian Olympic athletes brought home 82 medals. Student-athletes brought home 50 of those, or 62 per cent, even though student-athletes comprised only 55 per cent of the total team. Clearly there’s something about combining studies with sport, or something about the kind of person who does this, that leads to success.

And then there’s the bottom line. Most athletes simply can’t afford to concentrate exclusively on their sport.

“Very few of them will earn enough out of their sport to be able to put bread on the table,” notes Team Monash director Martin Doulton, who in his youth was an elite-level rugby player and cricketer.

“As an athlete, you’re focused on living the dream. But the reality is you’re only one injury away from retirement, and having a plan B is really important.”

Doulton also points out that university helps when things go belly-up. “Sometimes the university is a safe place to come to when you’re having problems on the track or the pool,” he says. “Because you have to filter and focus. That’s of benefit for the student athletes.”

Matt Chau, a badminton player from Monash who’s also at the Commonwealth Games, agrees. “Having these two aspects of my life which are so diametrically opposed to each other allows me to escape from the stresses of one part by absorbing myself in the other,” he says.

Georgia Griffith, an 800-metre runner representing Australia at the Commonwealth Games, is studying communications at Monash.

“I really enjoy having a balance between both my studies and sport, as I find it refreshing to be able to switch between the two. I also really enjoy the social side of both,” she says.

One thing all three athletes agree on is that this path is very challenging. They’re engaged in an extreme balancing act.

“I have to manage my time well, and at the same time I have to give 100 per cent focus to training well, eating well, doing all the basic lifestyle things to be 100 per cent come Games time,” says Heming.

His training involves two ‘on the table’ sessions per day, a few strength and conditioning workouts in the gym each week, and psychology sessions and breathing practices to help him hone his mental edge for the big moments in competition.

Table tennis often takes him overseas, too. “Table tennis isn’t a professional sport here in Australia, and the level of the partners, coaches and tournaments is limited. Before big tournaments I’ll go back to Europe to practise and play some tournaments.”

University support

Universiade medalist and Olympian Athletics hurdler Michelle Jenneke is one of the more recognisable Australian athletes to achieve high marks in both the classroom and athletics arena

Universiade medalist and Olympian Athletics hurdler Michelle Jenneke is one of the more recognisable Australian athletes to achieve high marks in both the classroom and athletics arena

None of it would be possible without the University providing a high level of flexibility and the opportunity for part-time study.

In 2004, Monash became one of the first signatories to the Elite Athlete Friendly University (EAFU), a program initiated by the Australian Institute of Sport that sets guidelines to help universities effectively support their elite student athletes.

“It’s about the role of the university in supporting that student athlete in becoming the best that they can,” explains Doulton. “I think supporting high-level performers is part of the Australian psyche.”

The Australian UniRoos Waterpolo team in action at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade

The Australian UniRoos Waterpolo team in action at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade

Unlike universities in the United States, Monash doesn’t recruit or offer scholarships to students based on athletic ability. They’re accepted on their academic merit alone. Once they’re on campus, Doulton’s team is there to support them.

“Team Monash is the first point of call for the mysteries of the university. We identify with them what their responsibilities are. We outline what the university’s commitment to them will be. It’s a mutual, shared commitment.”

Students can apply for funding to help cover travel or other costs associated with their sport. As representatives of the university, they can also apply for special consideration in Monash’s elite student performer scheme, which provides scheduling flexibility for exams and assignments.

“As an athlete, you’re focused on living the dream. But the reality is you’re only one injury away from retirement, and having a plan B is really important.” —Heming Hu

For Heming Hu, there was never any question that he would forgo university study to focus all his attention on table tennis.

“My parents have always been very big on education, so finishing university is important to me, and in their eyes as well,” says Heming. “Hopefully, once I’m done with that I can find a teaching job, perhaps to do with table tennis.”

You don’t have to be an elite athlete to reap the benefits of combining sport and study, notes Don Knapp, CEO of UniSport Australia. “There’s an abundance of research verifying the value of sport as part of the higher education student experience,” he says.

Australia takes on Russia in Men’s Basketball at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade

Australia takes on Russia in Men’s Basketball at the Taipei 2017 Summer Universiade

“EY sport/employment research and the Sheffield Hallam sport/graduate employment study have demonstrated that students who engage in sporting activities are happier, healthier and more engaged in university life. It’s also an employability bonus for students who articulate their sport-related skill development, such as leadership, team building and time management, as well.”

And don’t forget the fun factor. “It’s an extremely rewarding path that will teach you so many things – most of all about yourself,” says Matt Chau.

Heming Hu is excited about the Commonwealth Games. “It’s a good sort of two weeks, not just the sport, but the whole environment and the vibe on the Gold Coast.”

Anything in particular to watch out for?

He laughs. “Team Australia!”

Article republished courtesy of Monash University. Written by Monash University journalist Mary Parlange.